|

Maurice Durand’s book entitled “L’imagerie Populaire Vietnamiene” (Vietnamese Folk Paintings) was printed in black and white when he was 46 and reprinted in colour in 2011, 45 years following his death. |

|

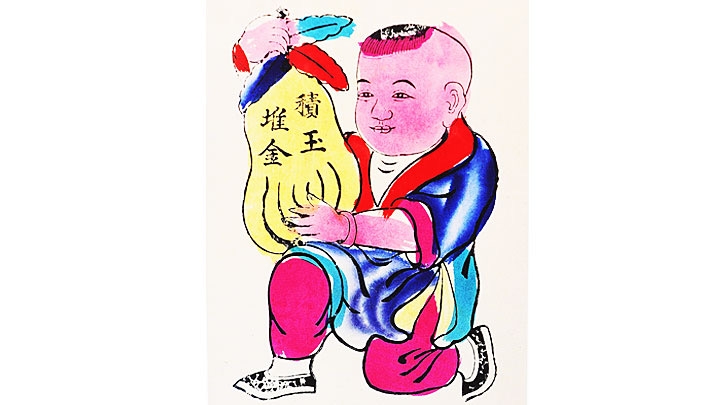

The scholar Durand from the French School of the Far East was an expert of history, culture and art. He left behind many excellent scientific works on Vietnam such as “Shrine and practice of hau dong (spirit mediumship)”, “Introduction to Vietnamese literature”, “Knowledge of ‘Vietnam”, “The history of the Tay Son period” and “Vietnam’s Nom script stories”. In 2017, M. Durand’s book “Vietnamese folk paintings” was translated into Vietnamese and published by the French School of the Far East and Ho Chi Minh City Culture and Arts Publishing House. It was warmly received and reprinted in 2020. M. Durand was good at Vietnamese and Sino-Nom (ancient Vietnamese scripts) and had a great passion on studying Vietnam. His father was Professor Gustave Durand, an expert in Chinese and Sino-Nom scripts. His mother was Vietnamese, Nguyen Thi Binh, from Kien An district of Hai Phong City. Born in 1914 in Hanoi and educated at the Sorbonne University in France, M. Durand returned to Vietnam to teaching and work in the French School of the Far East when he was 32 years old. He soon realised the unique beauty of Vietnamese folk paintings; thereafter he travelled around Hanoi and the neighbouring provinces to collect them. French scholars, such as P.Levy and L. Bezacier, as well as Vietnamese ones such as Tran Van Giap and Tran Huy Ba enthusiastically helped him and kept them at the French School of the Far East. At that time, folk paintings were very popular. His collection was exhibited in Hanoi in 1949 and then introduced to international friends at the Guimet Museum in France in 1960. In the introduction of the book, Durand wrote: “Vietnamese folk paintings allow us to draw conclusions about the cultural background of the Vietnamese people”. The statement showed his careful study about the paintings’ symbols throughout the decodes and their semantics. The sino-Nom illustrations highlighted Vietnamese people’s aspirations for prosperity, a spirit of study, production, religion and spiritual life. He divided the paintings into eight subjects, from religion and history to greetings and enchantments. M. Durand also studied deeply the minds of the people in the countryside. He was both buyer and producer of paintings. He demonstrated the customs reflected through the paintings in detail. The semantics of the Sino-Nom illustrations were expressed quite carefully. Through his survey in Hanoi in 1957, M. Durand realised that up to 300,000 folk paintings in do paper (paper made from the inner bark of the do tree) and 2,000 sets of paintings under various themes (including Vietnamese national heroes, religion, beliefs and four screens) were sold during the Tet (Lunar New Year) Festival. This number accounted for only sixth of the paintings made during the 1940-1945 period. These paintings have not been kept due to the difficulties of preserving paper paintings and the psychology of leaving old paintings to buy new ones for the new year. In addition, many trade villages where they were made were flooded, so both the paper paintings and printed boards were destroyed. Rarely do foreigners love Vietnam so much! The book “Vietnamese folk paintings” has been an invaluable gift to the cultural heritage of Vietnam and the world. The Academy of Inscriptions and Letters in France presented awards for this work. M. Durand passed away in 1966, but his huge collection of Vietnamese cultural heritage assembled both by e and his father was also stored at Yale University in the US. They were packed into 121 boxes containing valuable publications, translations, photos, documents and films for the study of Vietnam in ancient and modern times which had not been studied thoroughly. M. Durand’s collection of paintings is massive with many valuable ancient paintings that were well preserved so far. He realised their attraction lay in their rustic beauty and brilliant colours. The Chinese paintings were not as popular as the Vietnamese folk paintings during Tet Festival. Source: Nhan Dan Online |